The area of Ecuadoran life we, as a family, have the most frequent contact with is school. While the kids have adapted very well to their new school environment, Doug and I have had many a head-scratching moment trying to figure out what is intended by an assignment, why a particular school supply is required, or what the expectation of parents is in a given situation.

Before jumping in I should note that these observations are about our particular experience. I don’t have a good idea of how much they reflect the experience of expat families in other private or public schools, or that of Ecuadoran families. The school Gabe and Lucia attend is not a traditional Ecuadoran school. Rather it is a private bilingual (Spanish/English) school that was developed as an alternative to traditional schools that emphasize rote learning and have huge class sizes. The school is staffed with both Spanish-speaking teachers (primarily Ecuadoran teachers, although there are a few Spaniards also) and English-speaking teachers from England, Canada, and the US. Its “pillars” include the use of Spanish as a native language and English as an instructional language (about 40% of the time); an emphasis on the development of critical thinking and multiple intelligence; educational inclusion and a multicultural focus. Okay, so back to the things that jump out for us about our experience as school parents here.

Uniforms

Lucia and Gabe wear a dress uniform on Monday and Wednesday and a sports uniform (sweat pants and sweat shirt) on Tuesday and Thursday. On Friday, they can wear what they want. All public and private schools here use uniforms and most have these two iterations. I love the uniform for its simplicity. The kids know what they have to wear when and school clothes shopping is relatively easy. Not that this solves our school morning problems entirely. Somehow we still seem to have a hard time finding all the required pieces on the right day and keeping track of that school sweatshirt! The head scratching part has been the sheer number and variety of uniforms that are required. During the first semester of school all the kids had swimming once a week during the school day and were required to buy the swim suit uniform from the swim school, including the swim cap. This semester they have theater class instead and theater class requires an all-black outfit (leggings or sweat pants and shirt) - no images or designs allowed on the shirt. We enrolled the kids in an outside soccer school and it too requires a uniform. We opted out of having the kids participate in competitions with the soccer school. If they had, that would have required yet another, different soccer uniform.

Before jumping in I should note that these observations are about our particular experience. I don’t have a good idea of how much they reflect the experience of expat families in other private or public schools, or that of Ecuadoran families. The school Gabe and Lucia attend is not a traditional Ecuadoran school. Rather it is a private bilingual (Spanish/English) school that was developed as an alternative to traditional schools that emphasize rote learning and have huge class sizes. The school is staffed with both Spanish-speaking teachers (primarily Ecuadoran teachers, although there are a few Spaniards also) and English-speaking teachers from England, Canada, and the US. Its “pillars” include the use of Spanish as a native language and English as an instructional language (about 40% of the time); an emphasis on the development of critical thinking and multiple intelligence; educational inclusion and a multicultural focus. Okay, so back to the things that jump out for us about our experience as school parents here.

Uniforms

Lucia and Gabe wear a dress uniform on Monday and Wednesday and a sports uniform (sweat pants and sweat shirt) on Tuesday and Thursday. On Friday, they can wear what they want. All public and private schools here use uniforms and most have these two iterations. I love the uniform for its simplicity. The kids know what they have to wear when and school clothes shopping is relatively easy. Not that this solves our school morning problems entirely. Somehow we still seem to have a hard time finding all the required pieces on the right day and keeping track of that school sweatshirt! The head scratching part has been the sheer number and variety of uniforms that are required. During the first semester of school all the kids had swimming once a week during the school day and were required to buy the swim suit uniform from the swim school, including the swim cap. This semester they have theater class instead and theater class requires an all-black outfit (leggings or sweat pants and shirt) - no images or designs allowed on the shirt. We enrolled the kids in an outside soccer school and it too requires a uniform. We opted out of having the kids participate in competitions with the soccer school. If they had, that would have required yet another, different soccer uniform.

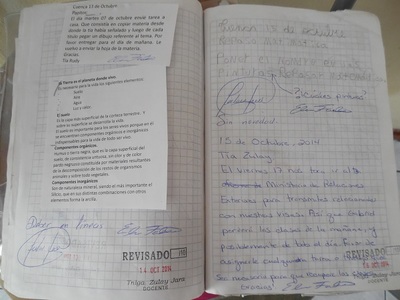

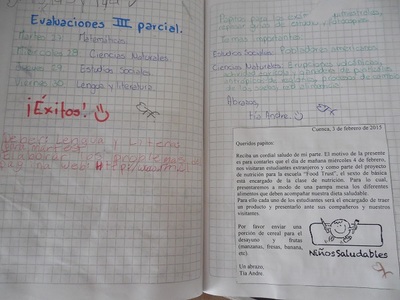

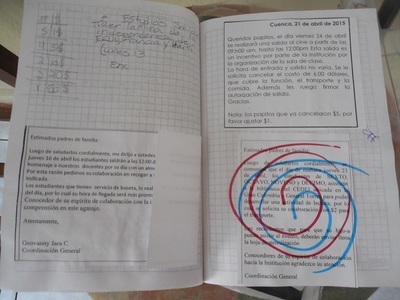

Mensajero.

Each kid has a small notebook with a plastic cover that goes from home to school and back again each day. At first I equated it to our Friday folder at home, but the mensajero is more intense. Teachers use it to send home important messages, send field trip permission slips, and to communicate homework assignments. Parents are required to sign each note to indicate it has been received. And it can be used to hold parents accountable. For example, in the purely fictional scenario that a parent read about an assignment and signed the note but the parent and child both spaced the assignment out, the teacher might paste in a new note commenting that the assignment was not completed and referencing the date and content of the first, signed, note. Yikes! Accountability for both the student AND the parents! The mensajero is also a convenient way to ask the teacher for clarification. Our confusion comes with the fact that not all assignments seem to be noted in the mensajero and not all teachers seem to use it the same way. So I’m never quite sure if we have missed something or if we are on track for that week.

Each kid has a small notebook with a plastic cover that goes from home to school and back again each day. At first I equated it to our Friday folder at home, but the mensajero is more intense. Teachers use it to send home important messages, send field trip permission slips, and to communicate homework assignments. Parents are required to sign each note to indicate it has been received. And it can be used to hold parents accountable. For example, in the purely fictional scenario that a parent read about an assignment and signed the note but the parent and child both spaced the assignment out, the teacher might paste in a new note commenting that the assignment was not completed and referencing the date and content of the first, signed, note. Yikes! Accountability for both the student AND the parents! The mensajero is also a convenient way to ask the teacher for clarification. Our confusion comes with the fact that not all assignments seem to be noted in the mensajero and not all teachers seem to use it the same way. So I’m never quite sure if we have missed something or if we are on track for that week.

“Queridos papitos”

This is the phrase almost all notes to parents begin with. I was surprised at the informality of the phrase, which translates literally to “my dear little parents”, although the diminutive is meant to be warm rather than demeaning. I’m used to the phrase now, although I usually take a deep breath when I see a note start with “Queridos papitos” because it seems that more times than not it is followed with a request to send some specialized school supply, needed immediately. More about this below.

School Supplies

Ecuador loves its specialized school papers: poster board, A4 sized cardstock; special drawing paper, etc. The bound notebooks used in classes come in a dizzying array of variations in regard to the number of lines in lined notebooks, graph versus lined paper, etc. The picture below shows the various notebooks arranged by type at our local papeleria. Big end-of-term assignments often require “papel ministro” which translates directly to “ministry paper”. Sort of the Ecuadoran equivalent of blue books, it is an oversized sheet, folded in half. Sometimes lined, sometimes in graph format, sometimes with a special “membrete” or header section. So far I think we’ve needed all the iterations, but never the same twice. Nonetheless, I’ve adopted the strategy of buying at least one extra of whatever is needed in the hopes of eliminating future emergency paper store trips when a special type is needed for the next day’s assignment. Luckily, there are 3 paper stores in our neighborhood and a big one near my work. Even if we don’t understand what the required paper looks like, we can usually get it easily as long as we can tell the store clerk what we need. They must be used to frantic parents coming in just before closing to get some specific form of paper.

We are often asked to send in some special item for a class project. Items we’ve been asked to come up with from one day to the next include: grass seed and sand; the advertisement from a magazine; a copy of a movie cover; a plant native to Ecuador; an abacus. You get the idea. And then there are the special materials for creative projects. The most extreme example was right before Christmas for which we had 3 days to find: an empty tin can, a dozen buttons, a meter of wide red ribbon, three toilet paper tubes (fortunately we had the Gallups visiting and we fed them a high-fiber diet), a bag of colored popsicle sticks, a three-liter plastic bottle (empty), a used magazine, the top of a shoe box, a used CD, a skein of yarn, and a large styrofoam ball.

Thanks to these “Querido papitos” notes I am constantly scanning the offerings of stores I pass while walking and making mental notes of where I can get various items if needed. At first I killed myself trying to get everything for the specialized list. But after grilling the kids in the wake of several “Querido paptios” notes I’ve learned that at least a few kids show up without the requested supplies, and some just bring in part of the list. So now I do only what feels doable given the timeframe and my state of mind to secure the requested item.

This is the phrase almost all notes to parents begin with. I was surprised at the informality of the phrase, which translates literally to “my dear little parents”, although the diminutive is meant to be warm rather than demeaning. I’m used to the phrase now, although I usually take a deep breath when I see a note start with “Queridos papitos” because it seems that more times than not it is followed with a request to send some specialized school supply, needed immediately. More about this below.

School Supplies

Ecuador loves its specialized school papers: poster board, A4 sized cardstock; special drawing paper, etc. The bound notebooks used in classes come in a dizzying array of variations in regard to the number of lines in lined notebooks, graph versus lined paper, etc. The picture below shows the various notebooks arranged by type at our local papeleria. Big end-of-term assignments often require “papel ministro” which translates directly to “ministry paper”. Sort of the Ecuadoran equivalent of blue books, it is an oversized sheet, folded in half. Sometimes lined, sometimes in graph format, sometimes with a special “membrete” or header section. So far I think we’ve needed all the iterations, but never the same twice. Nonetheless, I’ve adopted the strategy of buying at least one extra of whatever is needed in the hopes of eliminating future emergency paper store trips when a special type is needed for the next day’s assignment. Luckily, there are 3 paper stores in our neighborhood and a big one near my work. Even if we don’t understand what the required paper looks like, we can usually get it easily as long as we can tell the store clerk what we need. They must be used to frantic parents coming in just before closing to get some specific form of paper.

We are often asked to send in some special item for a class project. Items we’ve been asked to come up with from one day to the next include: grass seed and sand; the advertisement from a magazine; a copy of a movie cover; a plant native to Ecuador; an abacus. You get the idea. And then there are the special materials for creative projects. The most extreme example was right before Christmas for which we had 3 days to find: an empty tin can, a dozen buttons, a meter of wide red ribbon, three toilet paper tubes (fortunately we had the Gallups visiting and we fed them a high-fiber diet), a bag of colored popsicle sticks, a three-liter plastic bottle (empty), a used magazine, the top of a shoe box, a used CD, a skein of yarn, and a large styrofoam ball.

Thanks to these “Querido papitos” notes I am constantly scanning the offerings of stores I pass while walking and making mental notes of where I can get various items if needed. At first I killed myself trying to get everything for the specialized list. But after grilling the kids in the wake of several “Querido paptios” notes I’ve learned that at least a few kids show up without the requested supplies, and some just bring in part of the list. So now I do only what feels doable given the timeframe and my state of mind to secure the requested item.

Homework

This has been the biggest challenge for me, and the one in which I feel most lost. Part of that is bringing a U.S. mentality to doing homework – do the best work possible all the time. Here, it seems, homework is about completing the assignment with no bonus points given for volcanos that realistically ooze a lava-like substance – a simple triangular paper cut-out with colored lava flows will score a 10 out of 10. The other part is word meaning. I can, as can Lucia and Gabe, read the text describing the assignment and understand the vocabulary. Nonetheless, I’ve been tripped up by the meaning of those words. I’ve always thought “tarea” was homework, but here tarea is used to describe independent work done in class while “deber” is used for homework, and “leccion”, which I’ve always thought of as being a lesson, is typically a quiz or evaluative exercise.

Early on I was making sure the kids completed assignments and helping them understand what was expected. I wasn’t necessarily checking to make sure the assignment was done 100% correctly. After all, wouldn’t the teacher want to see if they were failing to grasp the concept being addressed? I was informed, though, that the expectation of parents here is that they make sure the assignments are completed 100% correctly. An interesting nuance in the purpose of homework and role of parents (also see Mensajero).

In addition, we often struggle to understand the underlying purpose of an assignment and thus how to tackle it or how much importance to put on it. Sometimes the kids have copied the assignment from the board, so there is always the question of whether something is missing or what else was explained in class that may have been missed. More often we don’t understand the intent. Why do you need to bring in laminated summaries of the French, US, and Haitian revolutions? Are we supposed to buy them, or are you supposed to create them? What is the purpose of the advertisement you are to bring in? Will this one on the tourism map of Cuenca, which we happen to have readily available, be okay? Thankfully I have several Ecuadoran coworkers with kids about Lucia and Gabe’s age who can be called on in emergencies to help me figure out what is needed.

There is also a big emphasis on neatness and presentation in assignments and homework. For Gabe, the word “Deber” needs to be in red pencil at the top of any homework, followed by the date (in blue) and then the assignment in regular pencil. The signs for mathematic operations also have to be in blue. Most of his homework has to be done in his special notebook that is half lined paper (for language assignments) and half graph paper (for math). Teachers have been aghast at both Lucia and Gabe’s less then beautiful handwriting, and they’ve both had help to improve it.

The School Calendar

At the beginning of the year I searched for the school calendar on the school website, frustrated that I couldn’t find it. Then I learned that the Ministry of Education publishes an official calendar. I asked for it and received it, but was warned not to put too much stock into it. Now I understand why. The president of the country apparently has the authority to suspend school and has done so several times to extend holidays. At Christmas we got an extra day, but were then required to make it up on a Saturday in February! Next week the kids have two extra days of vacation (not teacher’s though), leading up to International Labor/Worker’s Day which is celebrated worldwide on May 1st (except in the U.S., despite the date being based on events in US History ). The rumor is that the vacation days were granted to limit the possibility that university and high school students will organize the type of demonstrations that have historically marked the day. In addition to schedule changes determined at the national level we have several times received a note or email that class will be canceled later that same week, or even the next day(!), for purposes of teacher training or that special activities planned for a specific day will be moved to another. These last minute changes seem to have more to do with the organizational culture of the school than anything else, but are puzzling and frustrating to those of us used to planning out months in advance.

But are they learning?

Doug and I were clear when planning this year that our main priority in schooling would be a supportive environment for the kids and the opportunity to be immersed in Spanish and in Ecuadoran culture. Our official position is that we aren’t too concerned about academics this year, since the kids generally do well in school and can catch back up at home as needed. They have always been fond of online learning, like Cool Math Games, and recently we’ve had them doing Khan Academy. The kids really like their school, they language skills are flourishing, and they are learning about another culture: our stated priorities. But in about January I had an extreme moment (well, several moments) of panic about whether we should be making a more concerted effort to make sure the kids are up to speed on the academics they would be getting at home. There is much less focus on reading and writing in Ecuador than at home, and the math is totally different. It is hard to get a clear idea from the kids about what they are learning. So I dug in deep during their semester exams and was relieved to see, based on their exam scores and the content covered, that they actually are learning quite a bit. True, Gabe may never again need to know the major provinces in Ecuador, but at least they are successfully navigating a totally different educational world. And so are their parents, most of the time.

This has been the biggest challenge for me, and the one in which I feel most lost. Part of that is bringing a U.S. mentality to doing homework – do the best work possible all the time. Here, it seems, homework is about completing the assignment with no bonus points given for volcanos that realistically ooze a lava-like substance – a simple triangular paper cut-out with colored lava flows will score a 10 out of 10. The other part is word meaning. I can, as can Lucia and Gabe, read the text describing the assignment and understand the vocabulary. Nonetheless, I’ve been tripped up by the meaning of those words. I’ve always thought “tarea” was homework, but here tarea is used to describe independent work done in class while “deber” is used for homework, and “leccion”, which I’ve always thought of as being a lesson, is typically a quiz or evaluative exercise.

Early on I was making sure the kids completed assignments and helping them understand what was expected. I wasn’t necessarily checking to make sure the assignment was done 100% correctly. After all, wouldn’t the teacher want to see if they were failing to grasp the concept being addressed? I was informed, though, that the expectation of parents here is that they make sure the assignments are completed 100% correctly. An interesting nuance in the purpose of homework and role of parents (also see Mensajero).

In addition, we often struggle to understand the underlying purpose of an assignment and thus how to tackle it or how much importance to put on it. Sometimes the kids have copied the assignment from the board, so there is always the question of whether something is missing or what else was explained in class that may have been missed. More often we don’t understand the intent. Why do you need to bring in laminated summaries of the French, US, and Haitian revolutions? Are we supposed to buy them, or are you supposed to create them? What is the purpose of the advertisement you are to bring in? Will this one on the tourism map of Cuenca, which we happen to have readily available, be okay? Thankfully I have several Ecuadoran coworkers with kids about Lucia and Gabe’s age who can be called on in emergencies to help me figure out what is needed.

There is also a big emphasis on neatness and presentation in assignments and homework. For Gabe, the word “Deber” needs to be in red pencil at the top of any homework, followed by the date (in blue) and then the assignment in regular pencil. The signs for mathematic operations also have to be in blue. Most of his homework has to be done in his special notebook that is half lined paper (for language assignments) and half graph paper (for math). Teachers have been aghast at both Lucia and Gabe’s less then beautiful handwriting, and they’ve both had help to improve it.

The School Calendar

At the beginning of the year I searched for the school calendar on the school website, frustrated that I couldn’t find it. Then I learned that the Ministry of Education publishes an official calendar. I asked for it and received it, but was warned not to put too much stock into it. Now I understand why. The president of the country apparently has the authority to suspend school and has done so several times to extend holidays. At Christmas we got an extra day, but were then required to make it up on a Saturday in February! Next week the kids have two extra days of vacation (not teacher’s though), leading up to International Labor/Worker’s Day which is celebrated worldwide on May 1st (except in the U.S., despite the date being based on events in US History ). The rumor is that the vacation days were granted to limit the possibility that university and high school students will organize the type of demonstrations that have historically marked the day. In addition to schedule changes determined at the national level we have several times received a note or email that class will be canceled later that same week, or even the next day(!), for purposes of teacher training or that special activities planned for a specific day will be moved to another. These last minute changes seem to have more to do with the organizational culture of the school than anything else, but are puzzling and frustrating to those of us used to planning out months in advance.

But are they learning?

Doug and I were clear when planning this year that our main priority in schooling would be a supportive environment for the kids and the opportunity to be immersed in Spanish and in Ecuadoran culture. Our official position is that we aren’t too concerned about academics this year, since the kids generally do well in school and can catch back up at home as needed. They have always been fond of online learning, like Cool Math Games, and recently we’ve had them doing Khan Academy. The kids really like their school, they language skills are flourishing, and they are learning about another culture: our stated priorities. But in about January I had an extreme moment (well, several moments) of panic about whether we should be making a more concerted effort to make sure the kids are up to speed on the academics they would be getting at home. There is much less focus on reading and writing in Ecuador than at home, and the math is totally different. It is hard to get a clear idea from the kids about what they are learning. So I dug in deep during their semester exams and was relieved to see, based on their exam scores and the content covered, that they actually are learning quite a bit. True, Gabe may never again need to know the major provinces in Ecuador, but at least they are successfully navigating a totally different educational world. And so are their parents, most of the time.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed